As the number of unmanned aircraft systems (UASs), or drones, entering the sky continues to increase, proper integration of UASs into the airspace is a significant safety concern due to the potential for a UAS-airplane collision. Hobby drone users are the highest safety concern, as they may be unaware of or unconcerned with government rules and restrictions. Hobby drones are also relatively small and more likely to be ingested by an engine in a collision event.

We know drones are more damaging to planes than birds but how much damage can a drone cause to a jet’s engine?

According to professor Javid Bayandor, an expert on kinetics and collisions involving UAS, drones can cause extensive damage to a jet engine within seconds.

Javid Bayondor is the founder and director of the CRashworthiness for Aerospace Structures and Hybrids (CRASH) Lab at UB. The lab has built a database of more than 150 UAS models and investigated the potential damage they can cause to a wide range of manned aircraft during impact.

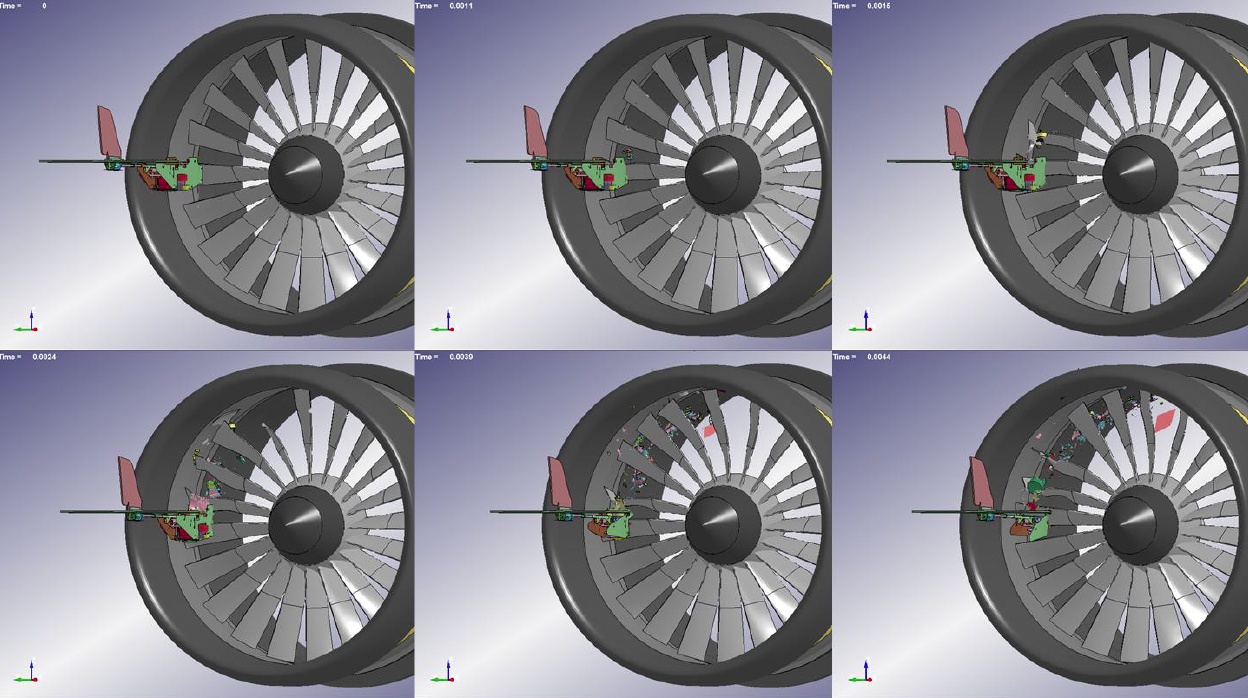

As seen through the CRASH Lab’s computer simulation, an 8-lb quadcopter drone can rip apart the fan blades of a 9-foot diameter turbofan engine in less than 1/200th of a second.

The CRASH Lab isn’t the only group studying drone-aircraft collisions, last year the Alliance for System Safety of UAS through Research Excellence (ASSURE) released a report on the severity of drone airborne collisions. ASSURE was in charge of the research that colluded with drones being more damaging to manned aircraft than birds.

Much like the CRASH Lab’s simulation, ASSURE’s simulation below shows a 4-lb fixed wing drone damaging the blades of a plane engine. In ASSURE's full report on drone aircraft engine ingestion, the research group also conducts simulations using a DJI Phantom 3 style quadcopter which lends similar results to this fixed wing drone.

The FAA is using ASSURE’s research to help develop operational and collision risk mitigation requirements for drones. While the FAA is still developing those requirements, the Government Accountability Office determined that the FAA must do more. It released a study on drones earlier this year with a clear warning in the title: "FAA Should Improve Its Management of Safety Risks."

Reports of close calls between drones and airliners have surged. The FAA gets more than 250 sightings a month of drones posing potential risks to planes, such as operating too close to airports. To put the problem into perspective, from more than 2000 drone reports called in last year, only 19 resulted in the pilot being tracked down and fined.

Currently, there are regulations and engine tests for bird and ice ingestions to ensure a plane can survive impacts with these objects. These tests and regulations cannot be directly transferred from birds and ice to UASs since the materials that compose a UAS are very different from the composition of birds. Some of the UAS components, including the motor, camera, and battery, can be far more dense and stiff than birds (which are typically modeled as fluid since they are over 70% water). Understanding the effects of a UAS-engine collision is critical for establishing regulations surrounding UASs, and will provide critical information to prepare the flight crew when this collision takes place.